AI in forensics: crime predictions, patrol robots

According to the International Association of Forensic Scientists, the implementation of artificial intelligence technologies increases the effectiveness of solving complex crimes by thirty to forty percent. Let’s explore how this happens.

Forensic science has always been a battle against time and incomplete data. Artificial intelligence solves these problems by processing huge amounts of information in minutes.

What does this mean for society and you personally? First and foremost—enhanced security and justice. More accurate and rapid identification of criminals reduces the likelihood of wrongfully accusing innocent people. These algorithms are free from prejudice and work exclusively with objective data. For law enforcement professionals, this means the need to master new skills. Modern forensic experts must be able to work with advanced analytical tools and critically evaluate results provided by artificial intelligence.

Now, I’ll tell you about examples of combining a traditionally conservative field like forensics with a new technology—artificial intelligence.

Acoustic gunshot detection technology

Gun violence in American cities is a real epidemic. It has claimed more than sixty-five thousand lives and injured hundreds of thousands of people in just the last five years. But the most shocking fact—according to SoundThinking company data, about eighty percent of shooting incidents are never reported to police! Criminals are evolving, exploiting gaps in the outdated emergency call system that has existed for more than fifty years. When people do call nine-one-one, they often can only provide vague or inaccurate information. This results in critical delays in helping victims and loss of valuable evidence.

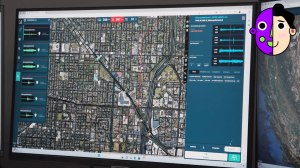

SoundThinking developed the ShotSpotter system—acoustic gunshot detection technology that fills this information gap. It uses a network of sound sensors connected to a cloud platform to reliably detect and accurately determine the location of gunshots through triangulation. Each sensor records the exact time and sound associated with impulse noises that might represent gunshots. This data is then processed by sophisticated machine learning algorithms to classify the event as a potential gunshot. Acoustic experts in the twenty-four-hour Incident Processing Center confirm that the events are indeed gunshots. They can supplement the alert with important information—for example, whether automatic weapons were used or if there were multiple shooters. The entire process takes less than sixty seconds from the time of shooting to the digital alert appearing in the Emergency Call Center or on patrol officers’ mobile devices.

The ShotSpotter system is already used in more than one hundred seventy cities worldwide and is highly valued by law enforcement as a critical component of strategies to prevent and reduce armed violence. Most clients are in the United States, including major cities like New York, Chicago, and San Diego, but last year Cape Town in South Africa was added to the client list. ShotSpotter protects a wide range of cities—from large metropolises like Las Vegas to medium-sized cities such as Boston, Denver, and Oakland, and even small towns with fewer than fifty thousand residents.

The implementation of ShotSpotter leads to impressive results in combating armed violence. The percentage of registered shooting incidents increases from twelve to ninety percent! Response time decreases from four and a half minutes to sixty seconds. Accuracy in determining the crime location improves from an error margin of more than three hundred meters to twenty-five meters. The percentage of shell casings found increases from fifty to eighty-nine percent. Victim transportation time is reduced from ten point three minutes to six point eight minutes. For example, in Oakland, California, thanks to ShotSpotter, help was provided to one hundred one victims in twenty twenty alone when no one reported the shootings.

Does ShotSpotter cause excessive police patrolling? According to the company, the technology allows police to respond more precisely, avoiding mass sweeps of entire blocks or neighborhoods. How accurate is the ShotSpotter system? From twenty nineteen to twenty twenty-one, the system had a cumulative accuracy of ninety-seven percent across all clients, including a very low rate of false positives—less than half a percent of all registered shooting incidents.

ShotSpotter technology represents a prime example of how artificial intelligence and acoustic sensors can transform traditional approaches to public safety. In a world where eighty percent of shooting incidents remain unregistered, such solutions can literally save lives by providing critically important time advantages for emergency services.

Technology for predicting potential crimes

We live in an era when the boundaries between public safety protection and total surveillance are becoming increasingly blurred. Facial recognition and behavior analysis technologies are penetrating various aspects of our lives, radically changing the very concept of privacy. Chinese company CloudWalk Technology has advanced further than most competitors, developing systems capable of not just identifying individuals but also predicting potential crimes before they occur. Such technologies raise fundamental questions about the balance between security and civil liberties, especially in the context of their application in regions with ambiguous human rights situations. In today’s world, algorithms increasingly become judges of human behavior, evaluating every movement through the prism of “suspiciousness” or “normality.”

Chinese company CloudWalk has developed a comprehensive system for government structures that uses advanced artificial intelligence technologies to detect and track people. This system is based on facial recognition and gait analysis technologies capable of identifying suspicious changes in behavior or unusual movements. For example, if a person walks back and forth across a certain area, the system might identify this as a potential sign of pickpocketing or reconnaissance for a future crime. Moreover, CloudWalk’s human-machine interaction platform has five key features: it functions as a “dream factory” with artificial intelligence experts, provides reliable intelligent decision-making, offers convenient and natural human-machine interaction, operates on its proprietary artificial intelligence operating system, and ensures secure data exchange.

CloudWalk was founded in twenty fifteen by Zhou Xi, a graduate of the University of Science and Technology of China with academic education in artificial intelligence and pattern recognition. CloudWalk’s technologies find applications in a wide range of areas—from financial institutions to government control systems. The company is the main provider of facial recognition technologies for the Bank of China and Haitong Securities. In twenty eighteen, CloudWalk signed an agreement with the Zimbabwean government to create a national facial recognition database and monitoring system that will track all major transportation hubs. According to company representatives, their system can identify potentially suspicious behavior patterns: “Of course, if someone buys a kitchen knife, that’s normal. But if a person later buys a bag and a hammer, this person becomes suspicious.” In May twenty twenty-three, the company released its large language model Comfort for beta testing, expanding its capabilities in artificial intelligence.

CloudWalk’s technologies raise serious concerns in the context of human rights protection and civil liberties. In twenty twenty, the U.S. Department of Commerce added CloudWalk Technology to its Entity List for its role in assisting the Chinese government in mass surveillance of the Uyghur population. According to American officials, CloudWalk Technology was “complicit in human rights violations and abuses committed during China’s campaign of repression, mass arbitrary detention, forced labor, and high-tech surveillance against Uyghurs, ethnic Kazakhs, and other members of Muslim minority groups in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.” In twenty twenty-one, the U.S. Department of the Treasury banned all American investments in CloudWalk Technology, accusing the company of complicity in facilitating the Uyghur genocide.

Technologies from companies like CloudWalk pose fundamental questions to society about the boundaries of technological interference in citizens’ private lives. Can algorithms truly predict criminal intentions? What is the cost of error when a person might be identified as a potential criminal based on analysis of their gait or shopping habits?

What do you think about the ethical boundaries of applying predictive control technologies? Can artificial intelligence algorithms objectively evaluate human intentions? I couldn’t find information about system glitches—though there must certainly be some with such volumes of data.

New concept of security technologies

Each year in the United States, more than one million violent crimes and over seven million property crimes are registered. Parking lots and car parks have become real crime hotspots, becoming places for car thefts, catalytic converter thefts, robberies, and vandalism. Particularly alarming is the fact that the traditional security model is experiencing a serious crisis. Fewer than one million law enforcement employees are physically unable to effectively protect three hundred fifty million citizens around the clock, seven days a week. This disproportion is exacerbated by a lack of coordination between nineteen thousand police departments and eight thousand security companies that operate without a unified national database of security best practices.

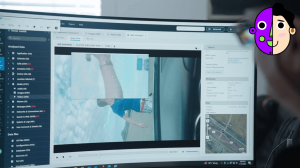

Knightscope has developed a fundamentally new concept of security technologies based on the idea of “Machine-as-a-Service.” The central elements of their ecosystem are Autonomous Security Robots, presented in several forms. The flagship K five model represents artificial intelligence in physical form. The robot autonomously patrols commercial properties and public spaces around the clock, without breaks, adding a layer of mobile perimeter protection and physical deterrence with intelligent “eyes, ears, and voice.” Stationary systems, such as K one Hemisphere, are designed for strategic placement at key points—from ATM vestibules to electric charging stations, elevator lobbies, and warehouse spaces. The K one Laser system deserves special attention, designed to extract maximum value from LiDAR technology. It provides high accuracy in detecting, classifying, and tracking people, vehicles, and objects, even in adverse weather conditions and low lighting. An important component of the ecosystem is the automated gunshot detection system AGD, capable of determining the location of gunfire with accuracy to within two meters within two seconds after the incident.

Knightscope has chosen a subscription business model for “Machine-as-a-Service.” This makes advanced security technologies accessible to a wide range of clients without the need for large initial investments. The company targets many market sectors—from airports and casinos to corporate campuses, hospitals, hotels, educational institutions, and public parks. Notably, almost fifty percent of deployed Autonomous Security Robots are used to protect parking lots and car parks, which highlights the relevance of the security problem in these spaces. The subscription model not only lowers the entry barrier for potential clients but also ensures constant software updates and technological support.

The implementation of Knightscope technologies leads to tangible results in public safety. The company’s clients report significant reductions in crime rates in protected areas—in some cases up to sixty percent in the first six months of use. In the city of Denver, from twenty eighteen to twenty twenty-one, thanks to Knightscope technologies, one thousand eight hundred forty-eight connections were established between found shell casings, and three hundred thirty-seven arrests were made. The company’s emergency communication technologies provide a critically important advantage in situations where seconds count. Instant notification of a shooting can significantly reduce emergency services’ response time and save lives.

Despite impressive technological capabilities, the implementation of robotic security systems raises serious ethical questions. The pervasive surveillance carried out by autonomous devices creates a new level of transparency in public spaces, blurring traditional notions of privacy. There is justified concern regarding algorithmic biases. What criteria does artificial intelligence use to classify behavior as “suspicious”? Questions also arise about the accuracy of facial and object recognition in real-world conditions. The psychological effect of the constant presence of observer robots in public spaces must also be considered. Will this lead to the formation of a society of total surveillance, where the very fact of observation becomes a mechanism of social control?

Are you ready to feel comfortable in spaces patrolled by robots? Or is it more familiar and reassuring with humans?

Artificial legal assistant

According to expert estimates, lawyers in court spend up to forty percent of their time on routine research work. And errors in legal analysis can cost clients millions of dollars and years of litigation. At the same time, there is an avalanche-like growth in the volume of legal information. In the United States alone, more than four hundred thousand new court decisions are published annually. This makes traditional working methods increasingly less effective.

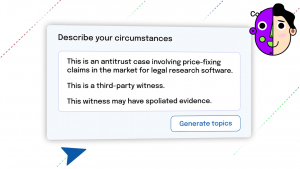

CoCounsel technology from Casetext represents a fundamentally new tool. It’s an artificial legal assistant specializing in precedent law research. Unlike publicly available artificial intelligence models, CoCounsel uses its specialized large language model. It works with Casetext’s proprietary legal databases, which guarantees the absence of “hallucinations” and fictional court cases. The system offers a unique set of specialized “skills.” These include searching for real laws to answer legal questions by providing a memorandum containing references to supporting sources; analyzing large datasets to extract critically important information; comprehensive analysis of contracts for compliance with requirements, with suggestions for specific corrections; and creating draft requests for interrogations.

Casetext was founded in twenty thirteen and has focused on applying artificial intelligence technologies from the very beginning. The company’s technological achievements were recognized by the prestigious publication Fast Company, which included Casetext in its list of “most innovative companies” this year. The company’s technological foundation is supported by a team of more than one thousand experts in generative artificial intelligence and machine learning, which guarantees constant improvement of the system.

The implementation of CoCounsel radically changes the economics of legal court practice, offering an unprecedented increase in work efficiency. The system can process documents at “superhuman speed,” completing tasks that previously took dozens of hours of qualified legal work in just minutes. According to research, using CoCounsel reduces the time spent on document analysis by eighty percent while increasing the accuracy of identifying problematic provisions by thirty-five percent. Using CoCounsel for preparation for court proceedings allows lawyers to analyze two and a half times more precedents in the same time, significantly strengthening the evidence base and increasing the chances of a successful case outcome.

Will this lead to the democratization of legal court services? Who bears responsibility in case of an error? The lawyer who relied on the technology, the system developer, or the neural network that formed the recommendation? These questions require not only technological solutions but also legislative initiatives regulating the use of artificial intelligence in the legal field.

In the future, we can expect the development of predictive analytics that will allow forecasting likely court decisions based on historical data and the specifics of a particular case. Of particular interest is CoCounsel’s potential in expanding access to justice through the creation of publicly accessible legal tools capable of providing basic consultations to citizens who cannot afford lawyer services. However, the key question remains open: Can artificial intelligence master the subtleties of legal interpretation, requiring not only logical analysis but also understanding of social context, historical evolution of legal concepts, and ethical nuances?

Comprehensive digital forensics tools

According to FBI data, in twenty twenty-two, almost three hundred sixty thousand cases of missing children were registered. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children received more than thirty-two million reports of suspected sexual exploitation of minors during the same period. The number of calls about missing children increased by sixteen percent compared to the previous year, reaching one hundred ten thousand appeals. These statistics are for the United States only, not worldwide. There, the numbers are much higher, unfortunately.

At the same time, law enforcement agencies, especially in small towns, are experiencing an acute shortage of budget funds and technological tools for promptly investigating such crimes. John Walsh, the well-known host of “America’s Most Wanted” and co-founder of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, notes: “I often say to myself, ‘My God, this predator’s lawyer is smarter and more technologically savvy than the police.’ They don’t really know the technology.” According to him, in conditions where human traffickers increasingly use advanced technologies and encryption to hide traces of their crimes, this technological gap becomes a critical public safety problem.

Cellebrite DI, based in Israel, has developed comprehensive digital forensics tools. The company’s flagship product—Cellebrite UFED (Universal Forensic Extraction Device)—provides unprecedented access to data on modern mobile devices. The company’s newest ecosystem, Inseyets, combines UFED capabilities with advanced extraction functions, including access to the full file system and decryption of encrypted content. Cellebrite technology can process colossal volumes of data. According to the company’s survey, an average smartphone contains more than thirty-two thousand images, one thousand videos, and sixty thousand messages. The Pathfinder system uses artificial intelligence to analyze this data, automatically identifying connections between devices, locations, and contacts of different individuals. Special attention is given to the Quick View function, which allows investigators to quickly assess the relevance of a device before its full processing, and the Triage sorting function, which helps prioritize the most critical devices based on customizable search criteria.

In twenty twenty-four, Cellebrite launched the “Operation Find Them All” initiative, under which the company provides its technologies free of charge to non-profit organizations involved in finding missing children, including the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children and The Exodus Road—an organization fighting human trafficking worldwide. According to Cellebrite CEO Yossi Carmil, this initiative goes beyond commercial interests: “This is a good mission. It goes beyond money.”

The results of applying Cellebrite technologies in real investigations demonstrate their high effectiveness. Kent Nielsen, a digital forensic investigator from the sheriff’s office in Texas, notes that the system significantly speeds up investigators’ work, especially when analyzing smartphones that can contain more than two hundred fifty thousand images. Instead of manually reviewing and sorting these images, the Pathfinder software automatically processes them, linking them to locations and data from other smartphones or cases. In twenty twenty-four, the Brazoria County Sheriff’s Office used Cellebrite technology as part of the multi-agency operation “Intercept” to rescue children who had become victims of human trafficking during the national college football championship. The operation resulted in the rescue of seven girls and the arrest of twenty-three suspects. Matt Parker, co-founder of the non-profit organization The Exodus Road, emphasizes the significance of the technology in international investigations, especially in countries where governments previously did not prosecute human traffickers. “When you’re fighting corruption on a global level, you need to gather an overwhelming amount of evidence that’s hard to ignore. You need to make the case absolutely irrefutable, and I’ll tell you, in thirteen years of experience… in hundreds of human trafficking cases, when we use Cellebrite technology and incorporate this technology into the judicial process, the success rate is significantly higher.”

Despite the undoubted benefit in fighting serious crimes, digital forensics technologies raise serious ethical questions. The ability to deeply penetrate citizens’ personal data creates risks of privacy violations. Technology companies working in the security field often face the dilemma of the dual-use nature of their products. The same tools that help save children and catch criminals can be used for mass surveillance of citizens. Additionally, the automation of forensic analysis processes, while increasing the efficiency of investigations, creates a risk of excessive trust in algorithms. When it comes to serious accusations that can deprive a person of freedom for many years, it is critically important to maintain human oversight of technological systems and their conclusions.

And I don’t know how to ensure a balance between citizens’ privacy and the need for effective investigation of serious crimes.

Platform for forensic investigations

Every day, about two point five quintillion bytes of data are generated worldwide—a figure that the human mind cannot even comprehend. Each crime today leaves a digital footprint, and the volume of these traces is growing exponentially. According to Interpol, more than eighty percent of modern crimes have a digital component requiring specialized investigation. Meanwhile, according to internal research by Magnet Forensics, investigators spend up to seventy percent of their time processing and analyzing digital evidence. There is a critical shortage of qualified specialists. On average, one digital expert handles forty-four investigations per year, creating an enormous backlog in this area. As a result, investigations are delayed, and justice is postponed—particularly dangerous in cases involving vulnerable populations such as children who have become victims of exploitation.

Magnet Forensics has developed a comprehensive digital platform for forensic investigations that combines advanced technologies for extracting, analyzing, and visualizing digital evidence. At the center of this ecosystem is Magnet One—a platform allowing investigators, forensic experts, prosecutors, and management to effectively collaborate on digital investigations. Their flagship algorithm, Magnet Axiom, provides recovery and analysis of data from mobile devices, computers, cloud storage, and automotive systems within a single case. And the Magnet Graykey technology, which emerged after the San Bernardino terrorist attack and was developed to overcome mobile device protection, provides access to the newest iOS and Android devices—often in less than one hour. Special attention should be paid to the recent implementation of Magnet Copilot—an artificial intelligence-based tool that helps identify synthetic media or deepfakes and analyze large volumes of data using a “question-answer” interface. Overall, the system allows selecting a specific data fragment, such as a message chain or web search history, asking a question about this data, and receiving an accurate answer with an indication of the source, which is critically important for confirming the authenticity of evidence in court.

The history of Magnet Forensics began with urgent necessity and humble roots. Jad Saliba, working as a police officer in Canada, was transferred to the digital forensics department, where he faced an acute shortage of tools for conducting digital investigations. Driven by the desire to solve this problem, he developed his own software tools, which proved so useful for law enforcement that in twenty eleven, Saliba left the police service and founded Magnet Forensics together with Adam Belsher, who previously held a leadership position at Research In Motion, the company that created BlackBerry. In parallel, in twenty sixteen, David Miles, Braden Thomas, Justin Fisher, and Sean Larsson, inspired by the difficulties of extracting data from the iPhone of a suspect in the San Bernardino terrorist attack, founded Grayshift and created the Graykey tool for accessing iOS devices, and later Android devices. In twenty twenty-three, Magnet Forensics and Grayshift merged under the common name Magnet Forensics. Today, the company serves more than four thousand clients in over one hundred countries worldwide, including law enforcement agencies, government institutions, and Fortune one hundred corporations that use their tools to investigate corporate fraud, intellectual property theft, and external threats such as ransomware and business email compromise.

According to data provided by the company’s clients, using the Magnet One platform reduces the time for processing digital evidence by sixty percent. Automation of routine tasks with Magnet Automate frees up to thirty working hours per week for qualified specialists, allowing them to focus on analytical work. Particularly significant results are demonstrated by the application of these technologies in combating crimes against children. In one documented case, the use of Magnet Axiom allowed the identification of more than two hundred victims of exploitation, leading to their rescue and rehabilitation.

Despite the undoubted benefit in fighting crime, digital forensics technologies raise serious ethical questions. Tools like Magnet Graykey, capable of overcoming mobile device protection, create a potential vulnerability for the privacy of ordinary citizens. And the use of artificial intelligence in evidence analysis, as in the case of Magnet Copilot, while increasing the efficiency of investigators’ work, creates risks of bias and opacity of algorithmic decision-making.

Special attention should be paid to the transparency of artificial intelligence algorithms used for evidence analysis and mechanisms for challenging their conclusions in court. Ultimately, the effectiveness of digital forensics will be determined not only by its technological capabilities but also by society’s trust in the fairness and ethical nature of its application.

Service for comparing DNA data

More than fourteen million people have already uploaded their DNA profiles to various commercial databases, hoping to learn more about their ancestors or find distant relatives. However, few of them realized that their biological information could ever be used by police to identify suspects in serious crimes. Approximately seventy percent of the Caucasian population in the United States can theoretically be identified through familial connections, even if their own DNA is not present in public databases. Such genetic transparency creates an unprecedented situation where one person’s biological material potentially reveals private information about dozens or even hundreds of their relatives. Traditional concepts of confidentiality and informed consent prove inapplicable in a context where one family member’s decision to share their DNA has far-reaching consequences for the entire family tree.

And here’s what can happen. GEDmatch is an online service created for comparing autosomal DNA data from different testing companies such as 23andMe, AncestryDNA, FamilyTreeDNA, and other world-renowned services. GEDmatch was originally intended to help “amateurs, professional researchers, and genealogists,” including adopted people searching for their biological parents. Here’s how it works: GEDmatch technology allows users to upload their DNA test results to identify potential relatives who have also uploaded their data. Participant names can be hidden using pseudonyms, but each account must have an associated email address. The tools available on the site include the ability to sort results by the closest matches with the user’s autosomal DNA; determine whether the user’s matches also match each other; use a genetic distance calculator; estimate the number of generations to the nearest common ancestor; and use various ethnic origin calculators.

By twenty eighteen, the GEDmatch database contained nine hundred twenty-nine thousand genetic profiles. The website received significant media coverage in twenty eighteen after it was used by law enforcement to identify a suspect in the high-profile “Golden State Killer” case in California. Other law enforcement agencies began using GEDmatch to investigate serious crimes, turning it into a “de facto DNA and genealogy database for all law enforcement.” This transformation occurred without users’ explicit informed consent, which caused negative reactions and led to the implementation of a voluntary participation system for law enforcement matching. In twenty nineteen, GEDmatch tightened its privacy rules, unilaterally requiring users to “consent” to sharing their data with law enforcement. However, for new uploads, the so-called “consent” is the recommended default choice, raising doubts about whether this can be considered true “voluntary participation.” Moreover, what exactly is being consented to is not clearly specified.

In twenty nineteen, GEDmatch was acquired by Verogen, a company specializing in forensic science. A new version of the existing site, known as GEDmatch Pro, was launched, now oriented toward solving crimes using more than one million two hundred thousand DNA profiles placed on the GEDmatch platform. According to BuzzFeed News, Verogen intended to monetize the site by charging for access to the database and DNA analysis tools. In twenty twenty-three, GEDmatch was acquired by Qiagen, beginning a new stage of commercialization of users’ genetic data.

In September twenty nineteen, the U.S. Department of Justice issued interim guidelines regulating when federal investigators or federally funded investigations can use genetic genealogy to track suspects in serious crimes. This first-of-its-kind policy covering the use of such databases in law enforcement stated that “forensic genetic genealogy” should usually only be used for violent crimes and for identifying human remains. Additionally, investigators should first exhaust traditional crime-solving methods, including searching their own criminal DNA databases. Under the new policy, investigators could not secretly upload a fake profile to a genealogy site without first identifying themselves. However, these guidelines applied only to federal investigators and federally funded investigations, not to state or local law enforcement agencies, which make up the vast majority of investigations.

Researchers predict that by twenty twenty-five, virtually all Americans of European descent may become identifiable through genetic connections, regardless of whether they have ever uploaded their own DNA.

Software for probabilistic genotyping

In modern forensics, DNA evidence is considered the “gold standard” capable of both accusing and exonerating a person. However, reality is much more complex than idealized notions. About seventy percent of DNA samples collected from crime scenes represent mixtures of genetic material from several people, which critically complicates their analysis. Traditional DNA interpretation methods require subjective decisions by analysts, where the human factor becomes a potential source of errors. According to independent research, different laboratories analyzing the same complex DNA mixtures can come to opposite conclusions. Match probabilities vary from one in several thousand to one in billions. Such discrepancies call into question the objectivity of the entire DNA evidence system. At the same time, the lack of standardized approaches to analyzing complex mixtures leads to valuable evidence being unused due to technical limitations, with the guilty remaining unpunished and the innocent—convicted.

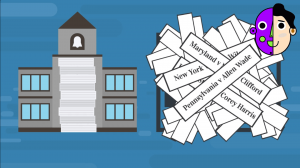

Cybergenetics has developed the revolutionary TrueAllele technology—software for probabilistic genotyping that fundamentally changes approaches to interpreting complex DNA evidence. At the core of TrueAllele are complex statistical algorithms that apply Bayesian mathematical modeling to analyze all DNA data, including low-level peaks usually discarded in traditional analysis. The system is fully automated, eliminating subjective human decisions and possible cognitive bias. TrueAllele can separate mixtures of DNA from multiple donors, determining their individual genotypes without using reference samples. Importantly, the program calculates the exact value of the likelihood ratio—a statistical indicator that determines the strength of evidence—and provides an error estimate for this coefficient, which significantly increases the evidentiary value of the results. According to the developers, TrueAllele can successfully analyze even degraded DNA and samples with very low concentrations of genetic material, which is especially important in cases of old unsolved crimes.

Cybergenetics was founded more than twenty-five years ago and pioneered the field of precise DNA mixture analysis. Over these years, TrueAllele technology has been validated in more than forty scientific studies, many of which were conducted by independent forensic laboratories and published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. This has created a solid scientific foundation for using the technology in real criminal cases. The system has already been applied in tens of thousands of criminal cases, both by prosecution and defense.

In one landmark case, the system was able to determine individual genotypes from a DNA mixture of five people, which was impossible using traditional methods. Thanks to this analysis, a serial criminal who had committed violence against twelve women was identified and convicted. In another case, TrueAllele helped exonerate an innocent person who had spent seventeen years in prison due to erroneous interpretation of a DNA mixture. The ability to compare evidence between cases allows identifying connections between various crimes, which is especially important for solving serial crimes. TrueAllele Database enables searching for matches between evidence and databases of convicted criminals, as well as conducting so-called “familial DNA searches,” when identification occurs through genetic relatives. Such automation of the analysis process allows processing up to one million samples per year, which significantly reduces the accumulated backlog of unexamined DNA evidence.

The main problem is that the software’s source code is a trade secret and not available for independent verification. Defense attorneys in criminal cases have repeatedly tried to gain access to TrueAllele algorithms to check their operation and potential errors, but the company consistently refuses such access, citing intellectual property protection. This creates a situation where defendants can be convicted based on evidence obtained using a “black box” whose operating principle they cannot verify or challenge. The second problem concerns the expansion of “familial DNA search” practices, when people can come under suspicion not because of their actions but because of genetic relatedness to a criminal. This raises questions about the boundaries of genetic information privacy and a person’s right not to be involved in a criminal investigation without their consent. Finally, the very high accuracy of the technology can create an illusion of infallibility of DNA evidence for jurors and judges, ignoring the fact that even the most perfect algorithms work with probabilistic models and have their limitations.

Visualization, photographing, and marking of fingerprints

Crime solving increasingly depends on scientific expertise, and dactyloscopy continues to be one of the fundamental identification methods. Each year, forensic experts process millions of fingerprints, spending tens of thousands of working hours on routine processes of detection, visualization, and marking. According to the International Association for Identification, a forensic expert spends on average up to seventy-five percent of working time on monotonous visual analysis of traces after chemical processing. This creates a colossal burden on forensic laboratories, leading to delays in investigations and accumulation of unexamined cases. Statistics show that in large forensic centers, the average processing time for one case can reach sixty days, and during peak periods—up to one hundred twenty days. Such delays have a direct impact on the effectiveness of justice. About twenty percent of solvable crimes directly depend on the timely processing of dactyloscopic evidence. Meanwhile, fatigue and decreased concentration during monotonous work can lead to overlooking important evidence.

Foster + Freeman, which has specialized in developing technologies for forensic science for more than forty years, has created the revolutionary AARI (Amino Acid Rapid Imager) system. This is an integrated solution for visualization, photography, and marking of fingerprints. The key innovation lies in using artificial intelligence to detect areas with papillary patterns. The system combines specialized lighting and imaging technologies optimized for working with traditional chemical reagents widely used in forensic laboratories to reveal latent prints on semi-porous materials like paper or cardboard. The integrated AI Assist function, developed using machine learning technologies, can scan a captured image in seconds and highlight areas with potentially identifiable papillary patterns. The system marks these areas either with contour frames or using a heat map, after which an expert can manually confirm the presence of fingerprints. This allows for significantly reducing time on tasks that previously could take hours to less than two minutes for a full processing cycle.

Implementing the AARI system in the workflow of forensic laboratories leads to substantial changes in productivity and efficiency. A process that previously could take up to thirty minutes per document is now performed in less than two minutes, representing a fifteen-fold increase in productivity. For a large laboratory processing hundreds of samples weekly, this can lead to savings of thousands of working hours per year. Beyond time indicators, the AI Assist system demonstrates stability in detecting areas with papillary patterns. Trained on thousands of fingerprint images over hundreds of hours, the system shows high sensitivity even to faint traces. In some cases, artificial intelligence can detect areas with papillary patterns that might have been missed by a tired human eye.

The introduction of artificial intelligence into such a sensitive area as forensic science raises a number of important social and ethical questions. On one hand, increasing the efficiency of processing dactyloscopic evidence potentially accelerates crime solving, which has a direct positive effect on society, including faster achievement of justice for victims and reducing the likelihood of new crimes by undetected wrongdoers. On the other hand, excessive trust in automated systems can create new risks. It’s important to note that the developers clearly position AI Assist as an auxiliary tool, not a replacement for human experts, emphasizing the necessity of manual verification of all fingerprints detected by the system.

Conclusion

Artificial intelligence in forensics is transforming the methodology of crime investigation, increasing the efficiency of identifying and analyzing evidence. Machine learning algorithms process colossal volumes of diverse data, revealing correlations and patterns inaccessible through traditional analysis. Computer vision systems significantly accelerate the processes of facial recognition on surveillance recordings, identification of firearms by traces on shell casings, and biometric data analysis.

Technological solutions based on artificial intelligence allow reconstructing the sequence of events at a crime scene and predicting potential criminal incidents in certain locations. The integration of neural networks with Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) databases opens new horizons in identifying suspects even with limited amounts of genetic material.

In the future, the development of these technologies will lead to the creation of comprehensive analytical systems capable of significantly increasing crime clearance rates and minimizing judicial errors. Artificial intelligence is becoming not a replacement for forensic experts but a powerful tool expanding their capabilities.

What ethical questions do you think arise from the implementation of artificial intelligence in forensics? Are you ready to trust algorithms with the analysis of evidence in criminal cases?